Posts in Category: Non-Weather

The RTTY Contest Problem

Sorry, I cannot pass this emergency traffic right now because there is a RTTY contest….

There is truly little in the HAM Radio aka: Amateur Radio world that I complain about, especially in the digital modes since I play around with them a fair bit, but there is one major exception. RTTY contests!

RTTY or Radio-Teletype is one of the original forms of text based digital communication implemented in both commercial and amateur high-frequency radio and even on the VHF band. While technology has come a long way and RTTY use has dwindled there are still RTTY enthusiasts just like CW (or morse code) enthusiasts and other users. So even though RTTY by all standards is an outdated old method of data transmission, there are still people out there who engage in RTTY conversations.

My issue does not lay with RTTY enthusiasts, but rather what happens when we have contests in specific modes and the effect these contests have on large portions of multiple HF bands.

It is no secret the three primary bands radio amateurs use are 80 meters, 40 meters and 20 meters. These bands have unique propagation characteristics that are dependent on the time of day, solar cycle and intended use. For example, 20 meters is a daytime band with a good low noise floor (relative to other bands) and signals can often travel thousands of kilometers. So, if you are floating in a boat out at sea some 2000km away from the shore and need to check email at 9AM, 1PM and again at 5PM, that is your band. During the evening hours and overnight the 40-meter band can really go the distance, the noise floor is usually not as good as 20-meter but not horrible by any means.

But what if you are floating in your boat and you are only about 800km from the shoreline during the daytime? The problem is, the 20-meter band may overshoot (literally) the Winlink RMS gateway station you want to connect to, so in that case you go lower in frequency to 40 meters and presto, it works. If you are even closer, 80 meters might be more reliable with faster data rates due to a better SNR although the noise floor is typically higher than 40 meters.

But what happens if there is a RTTY contest? Nothing, you will have a hard time getting through regardless of the band you use! Hopefully, you have some other way of getting in contact with the shoreline when you need parts or have an urgent email waiting for you from a land based relative!

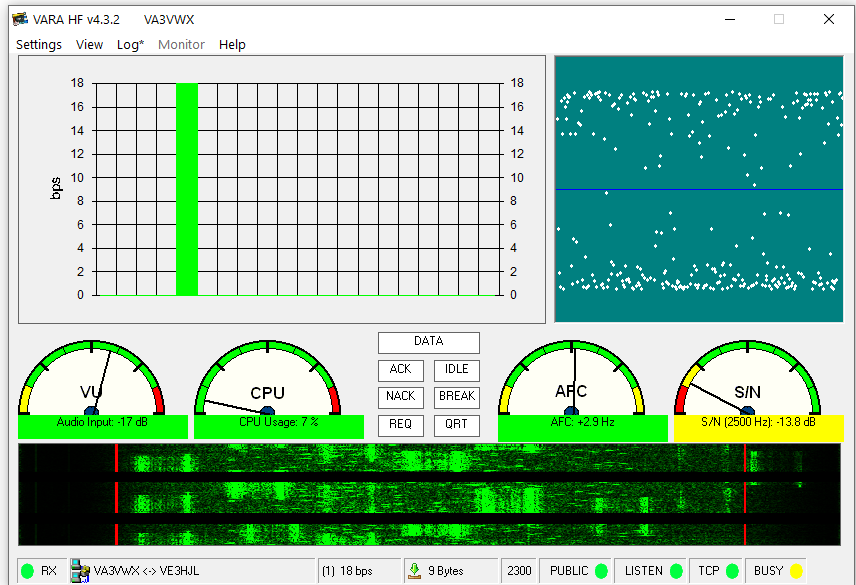

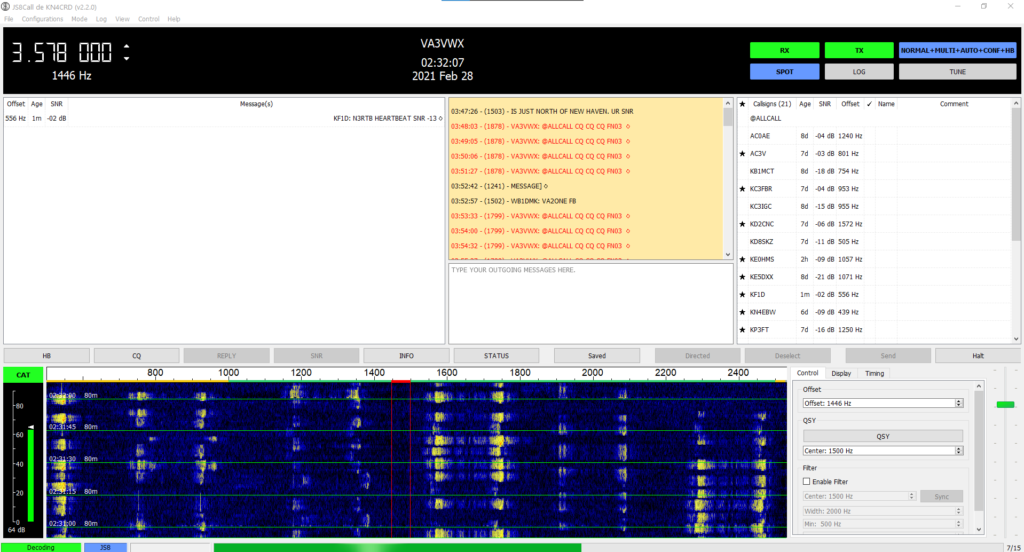

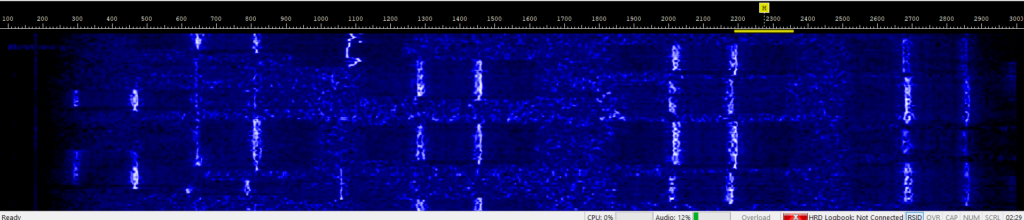

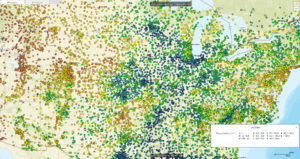

Okay, so you are floating in your boat and your VHF marine radio cannot reach anyone and the HF marine radio is acting up, but that is okay because you can relay messages through JS8CALL on your amateur radio and even get data into the APRS-IS network. You can literally use APRS to send a SMS via SMSGTE to your emergency contacts on shore who can then send you a Winlink email! At least they will know you are in trouble, right? Well, if you look at the waterfall above…. nope, good luck! JS8 which uses the FT8 protocol is robust, but it is always nice to hear heartbeat beacons that give you a SNR. If they can hear you, they let you know, and you know then your message has gone through!

Except, that is not going to work because the RTTY contest is bleeding all over JS8CALL and where all the relay stations reside and HB section too. GOOD LUCK!!! With RTTY signals washing all over, you are in trouble.

The problem with RTTY that no one likes to acknowledge is that it is a largely inefficient outdated mode. Unlike FT4, FT8, PSK31, JS8CALL, SSTV modes, Olivia etc. which all tend to be narrow signals and stick to little 2700 HZ wide portion of a single frequency or two frequency, RTTY signals are quite wide, noisy, do not tolerate interference well and do not stick to any small area or frequency during a contest.

When there is a FT8 or FT4 contest, everyone is generally confined to a small section of whatever band they are operating in and these signals do not interfere with the rest of the band. The same is largely true with PSK31 and other modes where users tend to be confined to small slivers of the band.

Meanwhile, with RTTY, it is like having a very wide FT8 signal and everyone just sits all over the place all day long, it is akin to using the whole digital and even a large chunk of the CW section of an HF band for FT8 with magnitudes of greater inefficiency.

Sure, contesting is fun, and I do not have anything against RTTY, but when it creates problems for all sorts of users across large sections of different bands, we have a problem. Now I understand, Winlink RMS sites sit across a multitude of frequencies in the digital section of the band plans and we cannot reasonably expect there not to be any overlap. I understand that, but that is not the problem, the problem is every single RMS gateway is crushed by RTTY traffic rendering all the HF Winlink system unusable and that is a problem. It even renders the tiny sliver of spectrum JS8 uses almost unusable, that is a problem. In fact, the only part of any band RTTY contesters seem to avoid is that part occupied by FT8 signals because even a weak FT8 signal will walk all over a strong RTTY signal and there is always a ton of FT8 traffic. So, all these contesters avoid it like the plague.

So here is my proposed solution:

All contesting bodies need to lay out a specific range of frequencies on specific bands to limit interference with other digital modes, end explicitly state that points will not be awarded for stations operating outside of said frequencies. There can also be time restrictions placed of specific parts of band to help get traffic through. Yeah, that means more RTTY signals will be packed together into a tighter space, but ham radio contests are supposed to be fun, they are not life and death, they are not important priority and welfare traffic. That is what people need to understand. When you need to use 80m, 40m or 20m for important traffic, the last thing you need is someone calling CQ CONTEST making it harder for that important traffic to pass. Just ask the CW users how they feel after a RTTY contest and you will know, something is seriously wrong.

The Great American Eclipse

*** All images in this post and many more are available for purchase through Alamy ***

If you’ve read my previous post titled “Chasing the Great American Eclipse” then you’ll know that I have been planning to chase this eclipse for years! This eclipse really was something special, and lived up to all the hype without the doom that was forecast.

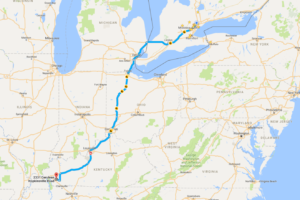

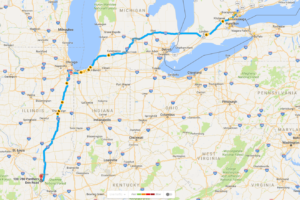

I left my home in Vaughan, Ontario on the morning of Saturday August 19th and made a b-line for the border in Port Huron, Michigan with my fiancee and mom who came along for the trip. I had booked a hotel room prior at the Super 8 in Peru Illinois for that evening. The distance from my home to the motel was about 940 km or a good solid 8 hour drive. I arrived around 11PM that night and had a pretty good sleep.

The following morning I hit the road at 11AM and headed straight for Des Moines, Iowa which is about 400km from Peru. I booked all my hotels roughly a month prior, I paced out the distanced and made sure I gave myself tons of flexibility to work around any cloud cover. I had initially intended to do most of the driving Sunday but figured it was a safe bet to stretch it out over two days instead. I spent the extra cash and booked the Ramada in Des Moines in order to treat myself to some luxury in the form of a nice swimming pool, good room service and half decent in house dining.

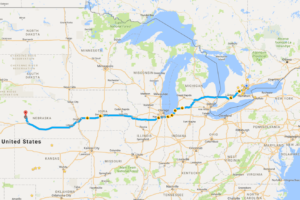

I initially intended to hit the road around 5AM targeting Beatrice Nebraska but the weather abruptly changed my plans. Basically there was a zone of instability running right along the path of the eclipse from central Nebraska down into northern Missouri. The risk of thunderstorms was a daunting reality! After a rather stressful couple hours looking at the evening models and data I decided that a 1AM departure would be necessary to head to the clear skies far west closer to the Wyoming border. I theoretically did not have to leave at 1AM but I wanted to give myself a buffer and there was a second problem emerging in the form of a big ugly MCS that was descending on Des Moines and had the potential to slow my commute.

We we’re able to load up the SUV with seconds to spare just as the MCS closed in with gusty winds and blinding rain. It was a pretty grueling drive from that point on, I was basically cutting through storm after storm for about 250 kilometers as everything lined up along the interstate in a big west to east line.

Eventually the skies cleared and the roads dried up just as I was crossing the border into Nebraska. What was a grueling drive suddenly became much more enjoyable! At this point it was 5AM and I was making good progress knocking off the kilometers. The only problem was that I did not have a concrete target. I was looking at real-time obs, infrared satellite data and early runs of the HRRR model to see what my best options were. I decided to head for Grand Island and make a move after that based on the weather observations. The distances involved were huge and while I felt I had plenty of time at the moment, it was just an illusion that would not last long with a mid morning deadline looming. I really wanted to be in position at least thirty minutes before the start of the eclipse to settle in and get all the gear sorted.

We made a quick fuel, food and coffee stop in Grand Island. The hotels were full, the streets were empty and the local Walmart which happened to lay only a few hundred feet off the center line of totality was rammed with campers spending the night while enjoying the luxury of food and fully serviced washrooms.

If you think about it, the Walmart really was a primo spot, no one would bug you, everything you needed was a one minute walk away, they’re open 24 hours and they had good wi-fi coupled with great cell phone coverage.

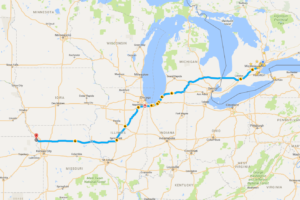

In retrospect I would have been safe watching the eclipse from Grand Island but at the time my main concern was some wispy high level cirrus pushing north from Colorado. While the cirrus may have been no big deal for most viewing the eclipse, it is absolutely catastrophic if you want good photos. Shooting through cirrus is like shooting through wax paper, you can do it, but everything comes out soft, there’s simply too much diffusion. So rather than risk having high level cloud problems, I decided to continue northwest towards Stapleton.

The drive up to Stapleton was pretty scenic, the sun eventually peaked out above the horizon and thin wispy high level cirrus came into full view. A shallow layer of radiation fog was also burning off rather quickly. I crossed the center line of totality several times along this highway while heading to Stapleton.

Things were great until the radiation fog began to get thicker, and thicker, and thicker. Eventually it was not really burning off and I could see it was increasing in depth. The blue sky above my head shrunk and began to turn into more and more of a milky white colour until it was simply gone. I was concerned but decidedly we pushed on with the northwestward journey. I certainly did not like what I was seeing but every ounce of conviction and instinct in my body told me not to worry, in the back of my mind I knew that it would burn off.

Eventually at about 9AM and 30 kilometers outside of Stapleton in the hilly terrain the fog began to break-up. I can’t tell you how relieved I was to see that, and to my surprise, the high level cirrus was all but completely gone. Unfortunately, my cell service had also vanished with the fog and clouds. I could make and receive calls but the internet data was running at a snails pace.

Suddenly, the weather observations I had been relying on were totally unavailable to me! Further frustrating was that as the fog burnt off, the clear sky was suddenly slowly being populated by stratus and stratocumulus. Again, I knew in the back of my mind mind that eventually this cloud too would burn off as vertical mixing increased but as with all weather, there’s never a guarantee that it’ll run on schedule and by this point it was already 9:30 AM and time was running out.

With no real data, I had to eyeball and “feel out” my odds, so I decided it was best and safest to continue pushing northwest towards the next town on the map known as Tryon. I actually had to do a double take, I kept reading Tryon but I wanted to say “Tyrone”. The rather thick strotocumulus slowly gave way to clearer patches and eventually the clouds began to turn into puffy fair weather cumulus. This was a great sign, but I could still feel the stickiness in the air, it was very very humid and ideally, drier is far better for less cloud and any potential fog.

I finally arrived in Tryon around 10:30 AM and began to hastily look for a parking spot. I edged my way to north side of town and found a farmer offering parking in his field, jackpot! I drove through and parked right on the eclipse centre line. I was right where I wanted to be with sunny skies and no real risk of cloud cover from any level.

Once parked I quickly began to unload the car and get my gear in order. I wanted to grab some photos of the sun before the eclipse and then capture the progression of the eclipse sequentially.

Probably 15 minutes after parking (around 11AM) some weak cumulus began to bubble up directly over my head. It was a little concerning since one poorly placed cloud is all that’s needed to ruin the adventure. I kept staring at the sky between getting setup and more cumulus began to bubble up above my head. I was sort of dismayed at this point since the sky above should have been totally clear, but my guess is that the residual moisture was so high in the boundary layer it was just coming back as cloud. There was little in the way of wind so the thermal heating was allowing the cloud to form right above me. At this point the eclipse was now probably 10 minutes away from starting and I was extremely concerned but then I had sudden relief. Clearing in the sky opened up to the north and the clouds were slowly drifting south. Eventually the clearing pushed in and the cumulus which was now beginning to dissipate moved south and away from the sun.

So once again I was relieved, the sky was clear and I hastily continued to setup my gear. The field I had chosen to park in (with a small fee paid to the rancher) began to steadily fill with vehicles. It was nice in a way since while I wanted to be free of distraction still having other people around (albeit at a distance) added to the feel of the atmosphere, it created a bit of a stadium feel, everyone was there for a spectacle of nature that was going to unfold.

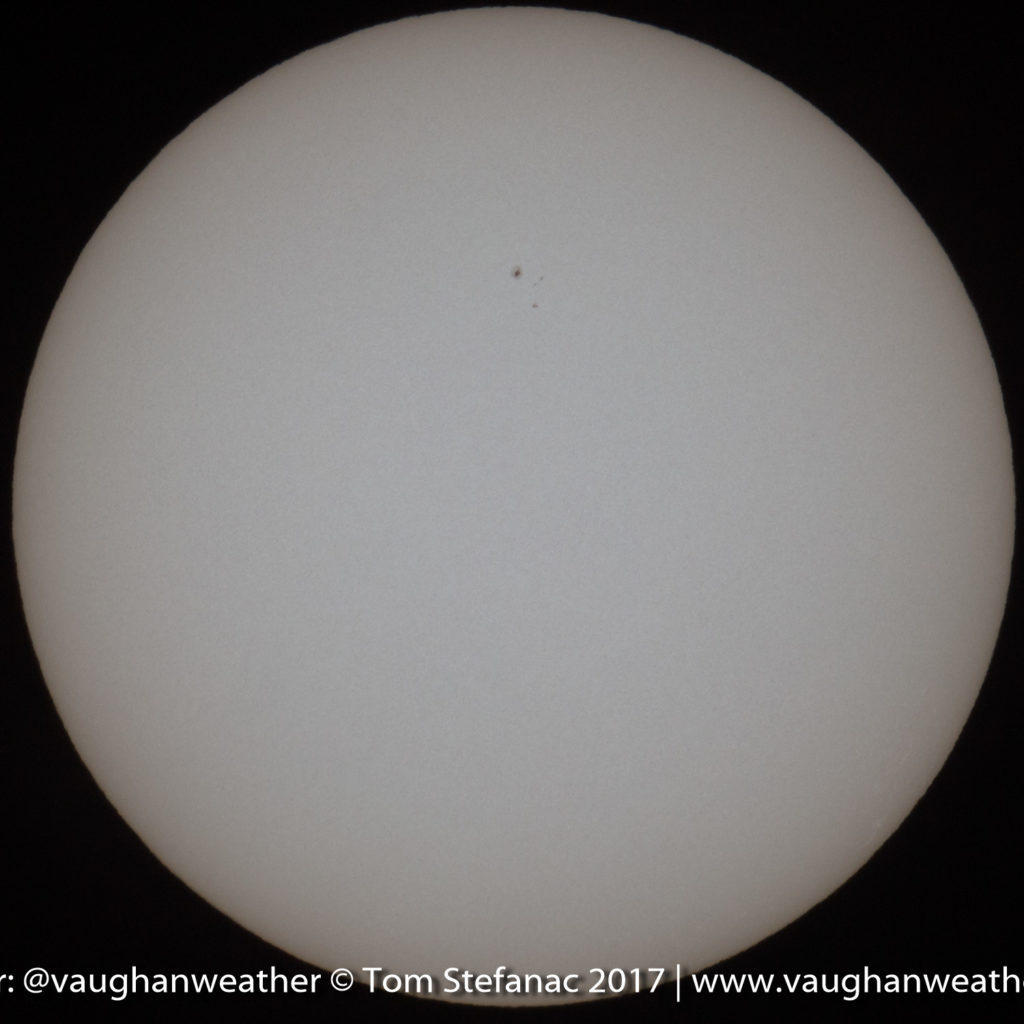

I snapped this photo of the sun at 11:17 AM, just 13 minutes before the start of the eclipse. I took it in the process of tuning the camera settings. It was weird looking at the sun, on the one had the day looked like any other day, there was nothing strange about it. There was no hint of the moon in the sky and sun looked like it always does.

I could not imagine that in a few minutes the moon would slowly begin to obscure it. It’s a hard feeling to explain, there’s nothing to indicate that anything you’ve been told is correct and while the math might add up there’s nothing within view to cumulatively show that math adding up.

I kept checking the time on my watch and using an application on my phone which calculates the eclipse event times using GPS data. It kept showing the start of the eclipse was getting closer and closer yet the sun and day felt so normal. As crazy as it sounds, I had this moment of doubt, I thought to myself “man, I really hope everyone is right and there’s going to be an eclipse today”. I know it sounds insane, but that thought really crossed my mind.

I kept looking at the sun through my protective glasses thinking to myself “I don’t believe this is going to happen”. I’m not a pessimist or anything and I understand math, science an how it plays into astronomy but being so use to weather where there is never any certainty, I was mistakenly subconsciously applying that same lens and frame of thought to a totally different process. Celestial bodies are in motion, we know their motion, it’s relatively easily predictable and there’s nothing to cause deviation. Whereas when I look at the weather, we simply have far less information, there’s far less certainty, much more going on and sometimes that thunderstorms I chase and forecast don’t blow up from clear skies.

I looked at my eclipse application again and the count down to the start of the eclipse read 3 seconds, 2 seconds, 1 second, zero…., the eclipse was starting. I quickly snapped a photo and dawned my eclipse glasses and there it was, the sun had a small sliver missing from the top right corner. The eclipse was actually happening and right on schedule. Up until this point it had all been theoretical, everything was a prediction, nothing was tangible. I had driven 2400 km on pure speculation and theory. I don’t know why it was so amazing to me that it was actually happening but suddenly the anxiety of possible failure seemed to fade away. I was actually relaxed and breathed a huge sigh of relief!

The hour and 23 minutes leading up to totality felt very long and truth be told, totality was what all the buzz was about, the partial obscuration was cool but I had seen it before. I wanted the main show to begin but you can’t rush nature. I filled the time by taking photos of the slow progression of the moon obscuring the sun, the sky slowly darkening, family group photos and generic things. I also took time to tinker with my GoPro and video camera. My camera shy fiancee opted not to be in any photos on this website sadly.

While watching the eclipse it was a scorcher! The sun was just beating down and I felt like I was melting. My mom (holding the umbrella) felt the same way, but at least she was able to get some shade. The scorching heat did not last very long though, about half way to totality the sun began to visibly wane in the sky and the day suddenly did not seem as bright as it was before.

As time progressed and more of the sun disappeared behind the moon the air began to feel slightly cooler. The air temperature itself at this point had not leveled out but what was occurring was more of a sensory perception illusion. The human body detects visible light, near infrared, UV radiation and long wave infrared (thermal infrared) as heat. That’s why standing out in the sun feels substantially hotter than standing in the shade even though there may not be any substantial change in your body temperature. Thus with the suns diminishing intensity, the body naturally has less light to interpret as heat and you feel cooler despite the air temperature remaining constant or even increasing.

At about 10 minutes from totality, the day still seemed pretty normal. Nothing odd was happening, except that the sun was visibly dimmer, but no dimmer than it would be with a moderate layer of cirrus diffusing the daylight. The nearby farm animals were acting normal, the cows were just grazing and going about their business, birds and insects were flying around and the eclipse gazing dogs were simply going about their business seemingly unaware of what was coming.

Things began to get interesting about 5 minutes away from totality, the daylight began to visibly fade rapidly and a sudden chill could be felt in the air, there was so little sunlight that the air itself began to cool quite rapidly dropping closer to the dew point and bringing the relative humidity right up. I could feel my hands and everything getting sticky in the growing humidity. The birds and large insects (dragonflies / butterflies) that were buzzing around earlier began to slowly vanish. The sky was also becoming eerie, it was growing darker but the sun still appeared very bright to the naked eye. It was an odd feeling but very much expected from my past experience with partial eclipses and literature I had read, but this however was on a much grander scale.

Suddenly everything changed just one minute away from the start of totality! A late evening darkness began to envelop the landscape and the sun now fading rapidly cast a glow that was about as strong as bright moonlight. I was busy getting ready for baileys beads, but I took a moment to look at the northwestern horizon and was amazed to see a huge zone of darkness rapidly expanding and seemingly growing in height consuming the horizon. It was the moons inner shadow (the umbra) approaching at a cool 2500 kph (1535 mph). I wish I had taken a second to photograph it but that thought at the time did not cross my mind. Suddenly, the dogs that were eclipse watching broke out barking like crazy, they finally realized something was not right. The cows nearby remained completely silent and motionless. By this point the air was now very cool, to the point where you almost needed a sweater and very sticky from the climbing humidity..

The clouds which had disappeared were also now starting to reappear in pockets! The reverse effect was occurring, while the sun heated and mixed the air to burn them off, the air was now cooling and the mixing had stopped essentially reversing the processing. Fortunately one stray cloud quickly passed without obstructing my view and the sky remained clear just as totality was about to set in. There was so much happening in such little time, I was changing camera settings and getting ready to blast off photos while above the stars one by one began to become visible, but totality was still not upon my location.

Even though about 99.5% of the sun was blocked, the last remaining rays that produce the diamond ring effect and baileys beads were so bright they still wholly overwhelmed the camera until totality was 10 seconds away. Then, and only then did the shimmering beads appear across the lunar limb and quickly fade one by one into darkness. At this point I was just blindly taking photos and full out staring at the sun with my eyes. It was just absolutely amazing!

As the last shimmering point of light vanished, darkness overtook the land! Then, the silence was broken by cheering and clapping, only to be outdone by the sound of a roaring jet engine as NASA scientists chased the eclipse from a WB-57 aircraft. It was incredible, words simply cannot describe the feeling in that moment, the surrealism of what was occurring, day had turned to night in a instant, there was twilight on the horizon, dogs were losing their minds, people were clapping, cheering and a jet engine could be heard roaring past on the edge of the umbra. It was just surreal!

The suns corona which was slowly becoming visible was now fully revealed! Red prominence’s could be see bending, twisting and blasting off into space, the orange-reddish glow of the suns chromosphere was brightly visible and the fine detail in the corona was visible giving it a wispy, wiry type appearance.

As I watched the corona, it’s subtle motion was revealed with a little bit of elasticity as as the suns gravity and varying magnetic charges played upon it. I would say it moved about as quickly as a vibrant aurora, but was far easier to observe with much more detail.

I did take a moment to take everything in, I did not want to experience the eclipse through the lens of a camera, I actually wanted to enjoy it as a tourist or the average Joe.

Looking around, I found the strange 360 degree evening sky to be somewhat fascinating and odd. It was basically like the sun was setting in every direction, or I guess contextually, no specific direction. I took a longer exposure of my mom looking at it and trying to get a photo on her phone. It was very dark, you basically needed a flashlight to see fine details, it was very much like night. The photo on the right contextually is more true to life as far as brightness goes but even so it’s still probably 1-2 stops brighter than it actually was. During totality the sky overhead was very dark, with virtually nothing other than the sun and stars visible.

This complete twilight horizon was going to be a short lived affair, as the moons shadow kept moving east, the western horizon began to grow bright and brighter signalling the approaching end of totality. With this in mind I made sure to take a variety of solar photos, one of the features that was quite rare and is not well shown in photographs are the suns prominences.

The prominences also known as filaments are basically charged strings of helium and hydrogen plasma that twist out along magnetic loops. They’re predominately anchored to the suns surface but can reach thousands of kilometers out into space. During the eclipse, several were visible around the edge of the sun appearing as a reddish pink colour in the visible light spectrum.

Photographing these microscopic features when compared to everything else requires a crisp aperture, ideally F8 to about F13, and and a relative fast shutter to beat down the light from the fainter corona blowing them out. Unfortunately there’s really no way to capture all the elements of an eclipse in a single photo due to the great variation in light intensity across different portions of the event.

Like all good things, even an eclipse must eventually end and time was running out, totality at my location had a mere duration of 2 minutes and 40 seconds. The west horizon in the span of about 10 seconds suddenly became very bright and edge of the moons umbra was fast approaching, totality was about to end. Then the first shimmers of bright sunshine made their way across the moons mountain to once again reveal baileys beads and the diamond ring effect.

I snapped off dozens of photos, I was certainly trigger happy but more so because the baileys beads event occurs so quickly and there is a huge difference between how the beads look every half second. It’s much like sports photography at a fast paced game, an image will change significantly in the span of just a couple seconds and baileys beads with any eclipse is no different.

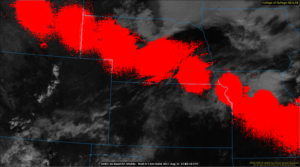

Before I knew it, the eclipse had ended and the moon was moving away from the sun, daylight was returning and it was gradually getting brighter by the second. I had made a mental note somewhere amidst my eclipse planning to make sure that I saved data from the news GOES 16 satellite. The satellite is an amazing piece of technology capable of beaming back images of the earth as frequently as every minute.

The new rapid update imagery with increased resolution gave a remarkable view of the moons shadow as it passed across the landscape. The satellite sees total darkness or near total darkness as white. Part of this is spectrum folding within the decoding software, but it gives a great idea of where total or near total darkness fell. What a year to have had the launch of this new powerful weather observation satellite.

As the eclipse slowly ended, the fellow eclipse watchers which had been parked in the field around me proceeded to leave, some rather quickly after totality had ended. A few die hard fans like myself stuck around to the very end, but truth be told there was not really a rush. There were literally tens of thousands of people rushing out to jam up the roads. Unlike a movie theater, sporting event or concert where everyone is coming from the same source, this was more like rush hour traffic where hundreds of people were coming out of different office buildings all along the route. There really was no beating the traffic.

What I found meteorologically interesting was the extent to which the eclipse had killed a nearby developing cumulus fields and induced a stratocumulus field. Despite the relatively short duration of the event, with the solar input dropping from a few thousands watts to nothing it’s easy to understand how significantly even this short duration can effect the larger weather pictures, at least for a time before the atmosphere recovers and convection resumes.

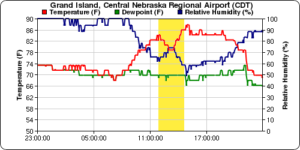

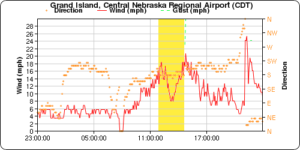

With the loss of daytime heating the wind fields also diminished substantially as the air calmed down and convective mixing slowed to crawl. There was no weather station in Tryon, but KGRE in Grand Island which also experienced totality had very similar weather conditions. You can see how the relative humidity approached 75% during totality with the air cooling from a pre-eclipse high of 30C / 86F down to a low of 21C / 71F just as totality was ending.

I was surprised at the extent of local cloud cover after the eclipse. Part of the cloud was a product of an impending MCS collapsing south from the north, but the majority of it was well ahead of the MCS and the result of boundary layer and low level saturation none of them

There were some clouds during totality but fortunately they stayed away from my field of view, so I really did dodge a couple bullets and luck did play a role.

Once the eclipse had fully ended we packed up and hit the road. Traffic was initially light, then gradually became heavier and heavier. Once we approached North Platte, Nebraska everything seemed to grind to a halt. This was an area where there were no alternative routes due to the local geography of a nearby river. So in that regard, jumping on a dirt back road was not an option, the only option was to tough it out with everyone else and try to make the best of a slow drive.

The town of North Platte itself was a zoo. There were lines for everything, the bathroom, fuel, food and anything else imaginable. I took two diesel jerry can with me which I filled up before leaving for the trip and fueled up in Grand Island earlier in the day. Between the superior range of diesel fuel, my near full fuel tank and two reserve cans we did not need to stop for fuel. A reassuring observation I noted was that the truck fueling stations were pretty desolate, so if I had to I could have just pulled up to a transport truck card lock and filled up. I have a truck fuel nozzle to vehicle grade nozzle adapter for just such an occasion.

We passed a couple of broken down vehicles and a few vehicles which looked to have run out of fuel while idling. I was critical to note that some peoples idea of an emergency fuel can was a little 5L / 1.5 gal container you’d use to fill up a push mower. In perspective if you’re getting 8L/100km on the freeway, in bumper to bumper traffic your getting something like 15 – 20L/100k or maybe even less. So even with amazing fuel economy you’ll still only get 60-70 km on that little tank and realistically maybe 15-20 km in bumper to bumper traffic. In rural Nebraska it’s not uncommon to drive 100 km or more without ever seeing a fuel station.

My logic was simple, driving a diesel vehicle and having 40L of reserve fuel plus a full 93L fuel tank would give me 133L total, enough to travel 1600 kilometers at 8L/100km realistically or 665 km at 20L/100km if I was getting abhorrent fuel mileage in stop and go traffic. That’s enough range to basically leave the state if need be and certainly enough to find somewhere to fill up. It also gave me the option to drive potentially hundreds of kilometers off-road if the apocalypse started.

Fortunately traffic thinned out south of North Platte and the interstate was moving very well. I had booked a room in Omaha at the local Microtel for the night to shorten the following days drive to the airport in Sioux City, Iowa where my mom would be flying out to connect in Chicago before arriving in Toronto. As luck would have it, we were blasted by the MCS (visible in the satellite loop above) late that evening while leaving the Texas Roadhouse restaurant near the hotel. Seeing as I had driven most of the night, my mom drove most of the time after the eclipse, although she had serious problems following the GPS nav commands. Thankfully my fiancee Jen kept her on track while I drifted in and out of consciousness in the backseat.

All in all the eclipse trip went out without a hitch and I never had to ditch any hotel reservations, all the planning was enough without any real over planning. The following day (August 22nd) I dropped my mom at the airport and my fiancee and I headed to back west across South Dakota to visit the Badlands near Wall and eventually the Black Hills and the Keystone Area.

Here is a short video showing the moments leading up to totality and it finally occurring.

Chasing the Great American Eclipse

I’ve been waiting pretty patiently for this eclipse since the early 2000’s when I decided to hunt down the next total solar eclipse that would arise in North America. What makes this eclipse so special is that it is not annular but rather total. Annular eclipses are cool, but the moon never actually completely covers the sun. With a total solar eclipse the moon fully covers the sun and a multitude of observable phenomenon occur which simply don’t during an annular eclipse.

For example, with a total eclipse not only is the transit of the moon visible with its slow disappearance but so too is the Baily’s Beads phenomenon which are the last slivers of sunlight squeezing past the various mountains on the moon. As the light vanishes suddenly, out of seemingly nowhere, totality begins and the suns corona emerges with red prominence’s visible on the edges of the disk. The sky become so dark that the brightest planets and stars become visible. It’s an incredible view!

But enough with the geek talk, let’s get down to business!

Chasing a solar eclipse is much like storm chasing. You have a general area of preference for viewing, you have a list of tools that you need, you have to be in the right place at the right time and lastly you need to know what your end goal is, what you want to get out of the eclipse. Fortunately, unlike storm chasing where we don’t really know what’s going on until those final few hours before the storm, with an eclipse we know when it’s coming, where it’ll be longest and the type of eclipse. The decision then becomes where exactly to head to watch it and will it give us what we want?

In my case, I want to have the longest duration possible for totality with the best chance of see the corona. Unfortunately, the area with the absolute longest duration is not necessarily the most favorable location when it comes to cloud cover. In this case both the areas presenting the greatest eclipse and greatest duration are in Southern Illinois and nearby Northwest Kentucky.

The problem with Southern IL and Northwest KY is that in August, especially mid to late August, the humidity tends to be very high! Plants are typically at their largest and foliage most extensive. This means transpiration rates are very high driving up local humidity values. There’s also abundant moisture that advects northward from the Gulf of Mexico which itself is beginning to get very warm by this point and posing a more substantial tropical weather risk. The high humidity values that arise locally and from afar make daytime cumulus clouds prevalent and the resulting thunderstorms a near daily occurrence. Couple this already cloud littered unstable environment with the lesser risk that the remnants of a tropical cyclone in the Gulf of Mexico may dive north and you have a recipe for great uncertainty with the potential for abundant cloud cover.

A thunderstorm isn’t even the problem so much as a weak cumulus field which could easily lead to just one single poorly placed cloud obstructing everything! Unfortunately, there’s simply too much humidity, vertical instability and resulting cloud cover. To put it in perspective, even if only the sky has 5-10% cloud cover, that’s too much! It just takes one cloud to ruin it all.

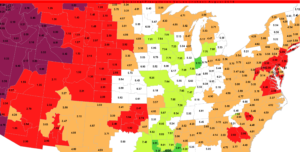

In order to avoid potential cloud cover, my eyes are drawn to the west, particularly the Nebraska/Missouri border where humidity values fall off east of the Mississippi but the duration of totality is still on the order of 2 minutes, 39 seconds, merely 3 seconds shorter than the greatest duration of totality in Illinois . Looking at the rainfall maps, it’s clear that the diminishing humidity values heading west translate directly into less rainfall which translates directly into less cloud cover at all levels. In fact if looking closely, it’s easy to note how the rainfall totals drop drastically west of Grand Island, Nebraska along the 98th Meridian. This is in part due to an increase in elevation, the dry downslope flow east of the Southern Rocky Mountains and diminishing vegetation density. This area is geographically where the Great Plains begin and the Central Lowland Plains fade off, the heavier forest cover tends to follow the moisture and naturally because of this sits east of the 98th, but the vegetation west becomes more grassy and shrubby meaning there simply is not as much transpiration to be had. The ground also becomes progressively more dusty and rocky, especially towards North Platte and Scotts Bluff which is directly reflective of the decreasing moisture in the atmosphere.

One other consideration which I will discuss in more detail a little later is the timing of the eclipse. The eclipse will begin in the west and travel towards the east. For areas that are far west into Oregon, morning fog, haze and low level stratus pose a threat since they may not burn off in time, and east of the Mississippi River where the eclipse will occur closer to noon, daytime heating will give rise to increasing cloud fields that will likely become denser with the potential for afternoon thunderstorms across Kentucky extending to the Atlantic cost of South Carolina.

All these factors combined suggest that the greatest potential for completely cloud free skies at all levels is generally from central through western Nebraska into Wyoming.

|

Given that Nebraska has the greatest potential for the least overall cloud cover, I need to consider driving options. Obviously the shorter the drive the better. The irony for me is that the two shortest drives are where the greatest and longest duration of totality occur. The two farthest options are where the least cloud cover from a climate stance occurs. It’s not an easy choice for me because I’m comfronted with the option of driving as little as 11.5 hours or as much as 19 hours. The eclipse also occurs progressively earlier west due to the time zone change and natural path. What this means is that there is no room for recovery. When chasing storms, the trend is that things farther west trigger later than things further east. So if storms are expected at 6PM EDT, 6PM CDT and 6PM MDT, you gain an extra hour heading west which each time zone since it goes from 22UTC to 00UTC. The eclipse is very different, it moves from west to east against the timezone change and very quickly, when the eclipse happens in Oregon it’ll only be a matter of 25 minutes before Nebraska see’s it. As a concrete example, the eclipse will start at 16:04 UTC (9:04 AM PDT) in Oregon on the Pacific coast and begin in central Nebraska just 30 minutes later at 16:34 UTC (11:34AM CDT). Then less than 20 minutes later it’ll begin in south central Illinois at 16:52 UTC (11:52 AM CDT). So even as I drive west and cross different times zones, I don’t actually really save any time, in fact I lose time since the eclipse moves from west to east. Logically this would suggest I should travel east, but again, the moisture increases and makes the cloud risk prohibitively high. Thus there is no room for error and driving calculations must exclude time zone variances. Of course anyone chasing the eclipse should strive to to be in position and setup well before the eclipse begins. It also means I need to choose a target location sooner rather than later should I head to Nebraska versus Illinois. |

|

Fortunately the one advantage weather junkies have over many others is the ability to forecast and really comprehend the weather. While you can always attempt to plan things based on statistics, the statistics only really matter if they’re right the day of and that’s a huge risk to take because statics are just the overall weather pattern for a given area over a certain time frame smeared together. The reality is that the weather always varies from day to day, minute to minute and even the most favourable statistic are no guarantee of anything. I like to think of statics and climate patterns as a loose guide, they help narrow down the viewing window, but can’t be used to fine tune it.

It’s important to realise that the most important decision making will occur in the final three days leading up to the eclipse. Then when weather junkies and eclipse chasers should be fine tuning their forecast. I’ll be looking for strong ridging, areas that are devoid of moisture at both the low, mid and upper levels as well as the upstream environment for any potential cloud producing weather.

I can’t stress how important it is to look for weather patterns that favour clear air at all levels with good visibility and are prohibitive to human induced cloud growth such as contrail development behind airplanes.

An important but lesser consideration for eclipse chasers will be air quality and smoke contamination from wildfires. I’ll be doing my absolute best to avoid any smoke plumes anywhere that could potentially set haze upon the viewing opportunity.

Photographic Tools

For me personally, a large part of the eclipse will be having the opportunity to photograph it.

I’ve been slowly building my photographic arsenal leading up to this day for years and as crazy as it sounds, the 800mm lens is one thing I specifically purchased primarily for the eclipse. If you had to ask me about what my motivation was to purchase it, the eclipse was really the single most important event that pushed me over the edge and believe me, if I could have afforded the Canon Ef 1200mm lens for $180,000 I would have purchased that too. But make no mistake, I’m not rich and the 800 really did break the bank.

I did consider telescopes before purchasing the Canon 800mm, but by the time you outfit a telescope and find one which has excellent optical quality you’re back in a similar ballpark with cost. The difference is, the lens is a lens which is great for everything from sports and nature to eclipses, while a telescope is really not useful for anything except celestial objects. That said, a 1000mm or 1500mm equivalent telescope is still slightly cheaper than an 800mm canon lens.

But having a big lens is just one part of the equation, understanding how to use the lens correctly is a whole different ball game.

Unlike everything else, the sun is not something you can just photograph. Because the sun is so bright, trying to shoot the sun with an unfiltered lens would result in the immediate death of the sensor exposed to it. Think about it like this, a lens really is just like a magnifying glass, it focuses concentrated light on a smaller area. If you can burn paper and set fire to hapless ants with a simple magnifying glass, just imagine what would happen to a camera sensor on the receiving end of that huge super amplified 800mm image. Needless to say, the results would not be good at all!

In order to protect the camera and lens, I’ve employed the use of a special daylight sunlight filter manufactured by MrStarGuy. It’s basically a specialized aluminum foil film sheet that significantly reduces the brightness of the sun only allowing a small but safe amount of light to pass.

The filter is similar in blocking power to a 1000x ND 3.0 filter. It’s so strong nothing else at all is visible except the sun when placed over the lens, and unlike a standard photographic ND filter, there is no colour cast. Most photographic ND filters tend to add a magenta tint to the image, the tint grows stronger as the blocking power of the filter increases. Thankfully, these colour casts are easy to remove with modern digital photography, but with the MrStarGuy system there is no need for colour correction as there is no tint which is a small but added bonus.

The filter to my surprise is optically very clean with no visible degradation to the image quality. The second thing that’s very important about this filter is that it is quickly and easily removable.

The filter is really only to be used during the first 95% of the eclipse, but once totality nears and the Umbra (moons inner shadow) approaches, it’s imperative to open the lens up in order to capture Baileys Beads, the suns corona and any prominences once totality occurs.

Then as the eclipse passes the midway point and 3rd contact begins I’ll quickly need to put the filter back on as totality ends and the umbra gives way to the penumbrra (moons outer shadow). This is the phase where the light intensity begins to grow again and the strength of the light can become damaging for optical devices, observers and camera sensors.

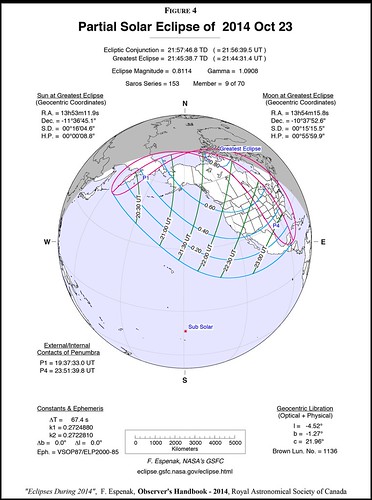

To give an idea of what the sun looks like when using a powerful blocking filter, here’s a sample from the October 23rd 2014 partial eclipse. Unfortunately just as the eclipse was starting to get going the sun set. But here you can clearly see how the sun looks with a filter as the moon passes in front. This photograph was taken using a 400mm lens and B+W ND 3.0 1000x filter. There is no colour correction as the sun was beginning to set and very orange.

Another important point to note is that a good sturdy tripod is really a must when shooting the sun, especially towards midday. Trying to hold a heavy piece of glass or anything up towards the sun is never easy! It’s better to let the tripod do the heavy lifting so you can focus on the photos.

Now a tripod is not a must, but a tripod becomes much more important during totality, especially if you’re interested in a somewhat longer exposure to capture all the fine detail in the suns corona. As a lens become longer, whether it’s a telescope or photographic lens, even the slightest shake or jitters become highly amplified.

There is one caveat, unlike a photograph of a static subject, the sun and moon are moving. This means that even with the use of a tripod, if the exposure is too long blurring will occur and the movement of the sun along the photographic plane increases with the magnification factor. So as a lens becomes bigger or more zoomed in, the shutter speed too must increase to prevent motion blurring, and this is something a tripod or image stabilizer cannot prevent, only a faster shutter speed has the power. Anyone into astrophotography or sports has dealt with motion blur. If you leave a shutter open too long star trails are the result. The longer the exposure, the longer the trails and the greater the blurring.

One solution to celestial motion I have not mentioned is a tracking motor/tripod system. There are telescopes out there with automatic tracking that are specifically designed for night sky photography. Tracking telescope/tripod systems are highly effective if setup correctly but very expensive and not typically designed for traditional photographic equipment. So the one solution to motion blur that does not involve a faster shutter is a tracking system.

During an eclipse the dark disc of the moon will give the sun a pacman type appearance as more and more of it is hidden out of view. During a total eclipse there are 5 phases, first contact, second, totality or max occultation, third and forth contact. First contact is the point when the moon first passes in front of the sun, second contact is around 50% coverage, totality or max occupation is the maximum possible coverage at a set location, and then third and fourth contact are the ending phases as the moon revels the sun once again and occultation returns to 0%.

Because the solar intensity varies greatly during an eclipse it’s very important to remain on top of light levels. The human eye is masterful at adjusting itself to the ambient light level, that’s why it’s easy to walk from a bright resturaunt out onto a dark street without noticing how much the luminosity has changed. Yet on a camera you’ll easily be pushing 20 or more F-stops between daylight and moonlight, and closer to 50 f-stops if looking at the sun without a filter. An eclipse is one of the most extreme natural light variances you can find in nature short of a volcanic eruption blocking out the sun. Because of this it’s important to always keep on top of your cameras metering and constantly adjust exposure levels as necessary.

You might also notice the sun in these images appears white, and that’s because it actually is. The sun is white because it emits all visible wavelengths of light. If you look a photo of the midday sun, or the sun without earths atmosphere obscuring it, it has a spectral colour balance of around 5600k which is basically white. Stars that are hotter than our sun tend to be a little more blue and stars which are cooler appear more red. From an artistic point of view, I personally prefer photographs of the sun to have a slight orange tint to them, it just feels a little more natural, what kid ever painted the sun white in their kindergarten class?

For more information and a great tutorial including exposure charts for various focal lengths, apertures and iso’s visit Mr Eclipse. This website has a plethora of highly useful information to help you plan and achieve the best possible results during the eclipse.

Helpful Resources & Links

Aurora Borealis – March 17th 2015

Solar Eclipse – October 23rd 2014