Hail Storms – An Educational Primer

Before I dive into the topic of hail and hail storms, I would like to clarify that there is not a singular storm type known as a hail storm. Hail is a product of convection and vertical growth cloud just as lightning, tornadoes, heavy rain and other thunderstorm phenomenon are part thereof. Storms which are called “hail storms” by the media, literature and other sources are noted for their production of large quantities of hail in addition to other things such as rain and lightning. So remember that hail is a part of a parent thunderstorm and not a storm in and of itself.

Now you might be asking yourself how bad can it possibly get inside the storms core?

Well that really depends on where you are, the type of storm and the atmosphere. In Southern Ontario thunderstorms tend to grow in moisture rich environments with high humidity. Storms that are typically found in moist air masses will produce less hail and more rain. There are a number of working theories but for one, moist air tends to be deeper and retain warmth so the effects of evaporative cooling aloft are diminished. Secondly, the updrafts become moisture-full sooner and the upward velocities are diminished limiting overall lifting power. Third, moist storms tend to begin dropping precipitating sooner, if not almost immediately compared to drier storms limiting the time for hail growth.

Classic Okalhoma Dryline Supercell with 4+ inch hail in the clearing / vaulted region just right of center

What has been observed generally is that dry environments and especially those with high elevations and low freezing levels produce more hail than moist environments with high freezing levels. In addition there are many theories around cloud microphysics that suggest atmospheres with less dust or particulate matter contain less nuclei for rain to form on and hail tends to be favoured.

Dry supercell storm with golf ball to baseball sized hail in Western Nebraska – hail shaft centre left with really big hail towards clearing on the left

Hail growth itself revolves around three primary theories. The first theory suggests hail rises and falls within a storm several times before falling to the ground. This up and down theory is supported by smooth stones and through the observed concentric rings of ice growth within a hail stone suggesting cycles of melting and freezing. The second theory is the suspension theory, where a hail stone sort of floats in an updraft gradually becoming heavier as it grows and eventually descending, then falling to the surface while banging into other lighter stones on the way down. These smaller stones and supercooled rain drops may stick to the larger hail stones creating a spiked appearance. The last theory is that a hail stone begins its growth low in the updraft while being thrown upwards rapidly and experiences rapid growth in the supercooled sub-freezing zone before eventually getting ejected out with downdraft and other precipitation. Stones that have a very cold soft white appearance and feel “soft” or graupel like support this theory.

Powerful dryline Panhandle Texas Supercell Storm – gigantic 3 inch hail just to the center right of the image

Unfortunately not one of these theories has been proven because hail is extremely hard to observe and there’s simply no easy, safe or conclusive means to “watch” hail growth in a storm. We can use radar to see a hail region develop but it’s hardly conclusive evidence when it comes to the actual formation process since the cloud microphysics in relation to the updraft structure and environment are critically important. I would argue that all three theories are likely correct and probably occur concurrently with one another in a storm through its life cycle.

There are also a number of geographic nuances we deal with here in Southern Ontario that places such as a the high plains of the U.S don’t deal with. The elevation across all of Southern Ontario is much lower ranging from 80 meters above sea level near the Southern Great Lakes to about 500 meters peak elevation in the Dufferin Highlands. Elevation changes around the bulk of the land mass lies in the 200-400 meter range. The average elevation of the plains in Colorado is around 1500 meters above sea level, that’s a whole 1km higher than the highest part of Southern Ontario and some parts of Colorado that are “flat” are actually +1700 meters ASL. The forecast implications of this high geography is immense since the 850mb level in Colorado is basically the ground, while here in Southern Ontario it’s 1.5km above the ground. Because of the elevation in Colorado the ground is much closer to the freezing level and hail has a far better chance of reaching the ground than it does in other places.

When you consider all the above factors, the largest hail you will typically see in Southern Ontario is 1cm or less with 2.5cm (quarter sized) hail occurring on occasion. Golf ball sized hail which is 4.5cm in diameter is possible and does occur a few times each year but only with the most powerful storms. The largest photographically documented hail in Southern Ontario fell on the afternoon of July 8th 2007. Fellow storm chaser Dave Patrick of www.ontarioweather.com was chasing a violent supercell which had produced several tornadoes and came across shredded trees between Mildmay and Listowel. When he ventured out to have a better look he found baseball sized hail which had cratered the ground. The hail was sitting for 20-40 minutes before he arrived and the largest stones were likely 3.25 inches / 8.3cm (teacup sized) before melting. His full chase log is online here.

It’s also important to remember big hail does not necessarily need a powerful supercell storm if the right elements come together. June 16th 2008 was a perfect example, the surface dew points were low so the air was pretty dry and the atmosphere above was super dry, very cold and the lapse rates were steep thanks to strong daytime heating! One storm popped up along a lake breeze boundary and began to rumble south into Vaughan. The storm produced tons of spiked 2-3cm hail denting cars and damaging crops. This storm formed in an environment that was far more reminiscent of the high plain and and so too was the resulting weather.

So you might be wondering where do you find hail in a storm?

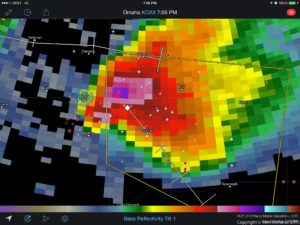

If it’s a squall line, the hail will likely blow in quickly on the leading edge with the heaviest rain and then quickly taper off. Single cell storms may produce heavy rain followed by a brief burst of hail which will diminish. Multicell storms will have various pockets of heavy rain/hail and vary a great deal. Supercell storms produce the biggest hail just to the north of the updraft core at the rear of the storm. A general rule of thumb is that the largest hail is going to be between the highest towers of the storms and the dark rain core.

How do you spot hail from a distance?

Typically hail will show up as a bright, band or streak in a darker rain core closer to the towering updrafts. This bright zone is referred to as a hail shaft. As a rule of thumb, the brighter the hail streak the larger the hail. Once a hail streak becomes invisible watch out! The general rule is that as hail size goes up, the visibility of the hail zone also increases because there is less diffraction of light. The spacing between the stones also increases further helping visibility get better. This is somewhat dangerous because unsuspecting motorists, chasers and others may wander into this clear zone when trying to escape the storms heavy rain core only to get pummelled by big hail. Another consideration is that anytime you’re sitting under the flanking line, especially when you’re closer to the area where the flanking line and parent storms begins precipitating then you’re at risk of getting hail, even if the sky appears to be clearing.